Now and then, a village with its modest spire, thatched roofs, and gable-ends, would peep out from among the trees; and, more than once, a distant town, with great church towers looming through its smoke, and high factories or workshops rising above the mass of houses, would come in view…

Néha-néha egy falucska is előbukkant szerény tornyával, nádfödelü kis kunyhóival s csúcsos háztetőivel s itt-ott egy-egy nagyobb város is odalátszott a messze távolból, melynek magas templomtornya szinte elmosódott a füstben, mely hatalmas gyárak és iparműhelyek kéményeiből kanyargott fölfelé.

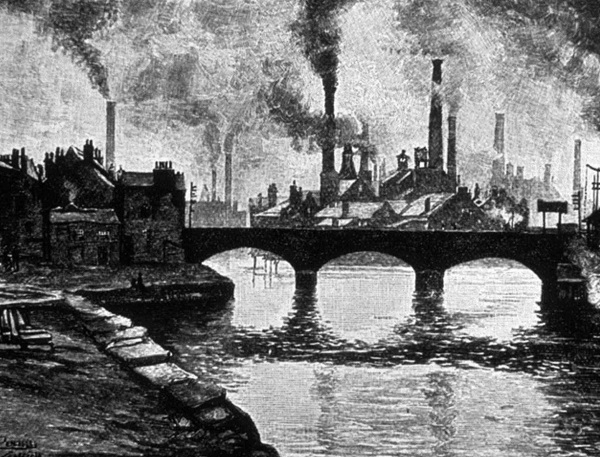

They had, for some time, been gradually approaching the place for which they were bound. The water had become thicker and dirtier; other barges, coming from it, passed them frequently; the paths of coal-ash and huts of staring brick, marked the vicinity of some great manufacturing town; while scattered streets and houses, and smoke from distant furnaces, indicated that they were already in the outskirts. Now, the clustered roofs, and piles of buildings, trembling with the working of engines, and dimly resounding with their shrieks and throbbings; the tall chimneys vomiting forth a black vapour, which hung in a dense ill-favoured cloud above the housetops and filled the air with gloom; the clank of hammers beating upon iron, the roar of busy streets and noisy crowds, gradually augmenting until all the various sounds blended into one and none was distinguishable for itself, announced the termination of their journey.

Lassanként közeledtek a céljuk felé. A víz megdagadt, piszkosabb lett; a város felől egyre több bárka haladt el mellettük, a szénporral és hamuval födött útak s a téglából épült kunyhók ipari város közellétét jelezték, később pedig egyes utcák és házak, valamint a gyárakból fölszálló füst azt mutatta, hogy beértek a külvárosba. Végre pedig a szorosan egymáshoz simuló háztetők és épületcsoportok, melyek rengtek a gépek munkájától, a hatalmas ipartelepek, melyeknek kéményéből piszkos, sűrű füst gomolygott elő, hogy gonosz fekete felhőként szétterüljön a város fölött; a hámorokból odahallatszó kalapácsütések, az utcai zaj, a tömeg zsivaja, mely lassanként egyetlen morajjá olvadt össze, melyben lehetetlen volt megkülönböztetni az egyes hangokat, — mindez azt jelentette, hogy elértek utazásuk céljához.

In a large and lofty building, supported by pillars of iron, with great black apertures in the upper walls, open to the external air; echoing to the roof with the beating of hammers and roar of furnaces, mingled with the hissing of red-hot metal plunged in water, and a hundred strange unearthly noises never heard elsewhere; in this gloomy place, moving like demons among the flame and smoke, dimly and fitfully seen, flushed and tormented by the burning fires, and wielding great weapons, a faulty blow from any one of which must have crushed some workman’s skull, a number of men laboured like giants. Others, reposing upon heaps of coals or ashes, with their faces turned to the black vault above, slept or rested from their toil. Others again, opening the white-hot furnace-doors, cast fuel on the flames, which came rushing and roaring forth to meet it, and licked it up like oil. Others drew forth, with clashing noise, upon the ground, great sheets of glowing steel, emitting an insupportable heat, and a dull deep light like that which reddens in the eyes of savage beasts.

A hatalmas nagy épületet vasoszlopok tartották, a felső falon nagy sötét nyílások voltak a beáradó levegő számára, és föl egész a tetőig kalapácsok zuhogtak, kohók sustorogtak, vízbe merített ércek zizegtek s mindenféle egyéb, előttük ismeretlen földalatti hangok hallatszottak. E komor helyen, mint megannyi gigász, úgy dolgozott egy csomó ember, mint a démonok, ide-oda járkálva a parázs és füst közt, fölhevülve, félig megaszalva a rettenetes tűztől, akkora szerszámokkal dolgozva, hogy egyetlen csapásuktól akármelyiknek a feje úgy szétment volna, mint a tojás. Néhányan a szén- és hamurakásokon hevertek szanaszét s fejüket fölfelé fordítva vagy aludtak, vagy a munkától pihenték ki magukat. Mások ismét a fehéren izzó kohóajtókat nyitották ki, szenet lapátoltak a lángba, mely zúgva csapott ki, hogy átvegye táplálékát s úgy fölszippantsa, mintha olaj lett volna. Ismét mások nagy zajjal és zörgéssel hatalmas izzó acéldarabokat vonszoltak a földön, melyek elviselhetetlen hőséget árasztottak. Olyan komor, sötétvörös volt a tüzük, mint mikor a vadállatok szeme szikrázik.

Philippe Jacques de Loutherbourg, 1801, olaj, vászon, Science Museum, London

In all their journeying, they had never longed so ardently, they had never so pined and wearied, for the freedom of pure air and open country, as now. No, not even on that memorable morning, when, deserting their old home, they abandoned themselves to the mercies of a strange world, and left all the dumb and senseless things they had known and loved, behind—not even then, had they so yearned for the fresh solitudes of wood, hillside, and field, as now, when the noise and dirt and vapour, of the great manufacturing town reeking with lean misery and hungry wretchedness, hemmed them in on every side, and seemed to shut out hope, and render escape impossible.

Vándorlásaik közben még soha úgy nem vágytak, nem lelkendeztek a tiszta levegő és a vidék szabadsága után, mint most. Nem, még azon az emlékezetes reggelen sem, mikor régi hajlékukat elhagyták, mikor egy idegen világ könyörületességére bízták magukat s maguk mögött hagyták azt a sok néma és érzéketlen tárgyat, mély ismerősük volt, mely hozzájuk volt nőve. Még azon a reggelen sem vágytak úgy az erdő, a halom, a mező üde magányára, mint most, mikor tele voltak a nagy gyárváros lármájával, piszkával, gőzével, a végtelen nyomorral és éhes elzüllöttséggel, melyet magukba szívtak s mely, úgy látszott, hogy elsorvasztja minden reményüket s lehetetlenné teszi menekülésüket.

A long suburb of red brick houses—some with patches of garden-ground, where coal-dust and factory smoke darkened the shrinking leaves, and coarse rank flowers, and where the struggling vegetation sickened and sank under the hot breath of kiln and furnace, making them by its presence seem yet more blighting and unwholesome than in the town itself—a long, flat, straggling suburb passed, they came, by slow degrees, upon a cheerless region, where not a blade of grass was seen to grow, where not a bud put forth its promise in the spring, where nothing green could live but on the surface of the stagnant pools, which here and there lay idly sweltering by the black road-side.

Keresztülmentek egy hosszan elnyúlt külvároson, hol vörösek voltak a háztetők, hol a kőszénpor s a gyári füst teljesen belepte s összezsugorította a faleveleket, hol el volt csenevészedve a növényzet s alig tudott tengődni az izzó kohók meleg levegőjében, mely itt a lombok és virágok közt még gyilkolóbbnak és egészségtelenebbnek tetszett, mint a városban. Keresztülmentek egy hosszú, unalmas, messze elnyúló külvároson s oly barátságtalan tájra érkeztek, melyen nem volt látható egyetlen fűszál, hol egyetlen bimbó vagy rügy sem hirdette a tavaszt, hol nem lehetett egyéb zöldet látni, mint a mocsarak békanyálas zöld felszínét, mely a fekete országút mentén itt-ott feltünedezett.

Advancing more and more into the shadow of this mournful place, its dark depressing influence stole upon their spirits, and filled them with a dismal gloom. On every side, and far as the eye could see into the heavy distance, tall chimneys, crowding on each other, and presenting that endless repetition of the same dull, ugly form, which is the horror of oppressive dreams, poured out their plague of smoke, obscured the light, and made foul the melancholy air. On mounds of ashes by the wayside, sheltered only by a few rough boards, or rotten pent-house roofs, strange engines spun and writhed like tortured creatures; clanking their iron chains, shrieking in their rapid whirl from time to time as though in torment unendurable, and making the ground tremble with their agonies. Dismantled houses here and there appeared, tottering to the earth, propped up by fragments of others that had fallen down, unroofed, windowless, blackened, desolate, but yet inhabited. Men, women, children, wan in their looks and ragged in attire, tended the engines, fed their tributary fire, begged upon the road, or scowled half-naked from the doorless houses. Then came more of the wrathful monsters, whose like they almost seemed to be in their wildness and their untamed air, screeching and turning round and round again; and still, before, behind, and to the right and left, was the same interminable perspective of brick towers, never ceasing in their black vomit, blasting all things living or inanimate, shutting out the face of day, and closing in on all these horrors with a dense dark cloud.

Mennél jobban behatoltak ennek a szomorú környéknek a homályába, annál komorabb, nyomasztóbb érzés lopódzott lelkűkbe, búskomorsággal töltve el őket. Ameddig a szem csak látott, mindenfelé nagy hámorok álltak, végtelenül ismételvén önön magukat s versenyt fújták magukból a füstöt, elhomályosítva a napot s megmételyezve az amúgy is sűrű levegőt. Az útszélen óriási hamugátakon különös alakú gépek forogtak és nyögtek, mint valami megkínzott teremtések; vasláncaik csörögtek, sírtak s fel-alá járó hatalmas kerekeik dübörgésétől megrendült a föld. Azután nyomorúságos házikók tünedeztek föl, korhadt falak megtámasztva, tető nélkül, ablakok nélkül, tele korommal és piszokkal, de azért mégis laktak bennük. Azután ismét komor gépszörnyetegek következtek, dohogva, búgva, zakatolva s jobbra és balra hatalmas kémények látszottak, melyek szakadatlanul okádták barna füstjüket, elpusztítva minden élő és élettelen tárgyat, elhomályosítva a Nap arcát s az egész tájat sűrű fekete felhővel vonva be.

But night-time in this dreadful spot!—night, when the smoke was changed to fire; when every chimney spirited up its flame; and places, that had been dark vaults all day, now shone red-hot, with figures moving to and fro within their blazing jaws, and calling to one another with hoarse cries—night, when the noise of every strange machine was aggravated by the darkness; when the people near them looked wilder and more savage; when bands of unemployed labourers paraded the roads, or clustered by torch-light round their leaders, who told them, in stern language, of their wrongs, and urged them on to frightful cries and threats; when maddened men, armed with sword and firebrand, spurning the tears and prayers of women who would restrain them, rushed forth on errands of terror and destruction, to work no ruin half so surely as their own—night, when carts came rumbling by, filled with rude coffins (for contagious disease and death had been busy with the living crops); when orphans cried, and distracted women shrieked and followed in their wake—night, when some called for bread, and some for drink to drown their cares, and some with tears, and some with staggering feet, and some with bloodshot eyes, went brooding home—night, which, unlike the night that Heaven sends on earth, brought with it no peace, nor quiet, nor signs of blessed sleep—who shall tell the terrors of the night to the young wandering child!

Hát még az éjszaka milyen volt ezen a borzalmas tájon! Éjszaka, mikor a füst tűzzé vált, mikor minden kémény szikrát okádott, mikor az olyan helyek, melyek nappal fekete barlangoknak látszottak, izzó vörös fényben égtek, mikor rejtelmes alakok jártak ide-oda a lobogó fényben, durván, rekedtek kiabáltan egymásra, mikor a különös gépek zaja szinte megkétszereződött a sötétségben, mikor közelükben az emberek sokkal vadabb alakoknak látszottak, mikor a foglalkozás nélküli munkások csoportonként ődöngtek ide-oda vagy a fáklyák fényénél vezetőik körül csoportosultak, a kik izgató szónoklatot tartottak nyomorúságukról s erélyes tettekre tüzelték őket; mikor fegyverrel és fáklyával fölfegyverzett őrültek az őket visszatartani akaró feleségeik könnyei és rimánkodásai ellenére kirohantak a sötét éjszakába, hogy rémületet és pusztulást keltsenek mindenfelé. Milyen borzalmas volt ez az éjszaka, mikor durván összetákolt koporsóval megrakott kordék zörögtek végig az úton (mert a ragályos betegségben dús aratása volt a halálnak), mikor árvák sírtak és őrült asszonyok csikorgatták fogaikat, – az az éjszaka, mikor néhányan enni, mások inni kértek, hogy elfojtsák elkeseredésüket, mikor némelyek könnyezve, mások támolyogva, ismét mások vörösre dagadt szemmel, komor gondolatokba mélyedve ődöngtek szanaszét; – ez az éjszaka, mely bár az égből szállt alá a földre, nem hozott magával békét, nyugalmat és üdítő álmot. Ki tudja elképzelni, hogy ez az éjszaka mennyi rémületet keltett a fiatal vándor gyermekben!

William T. Russell, 1843