Saját jel · Signs of Her Own

Részlet · Excerpt

Semleges látás Keserü Ilona festészetében

Keserü a semleges látás mestere. A semleges látásnak nincsen szüksége tolmácsra és fordításra. Festészete ezt a szintet szólítja meg, egyszerre a nyelv előttit és a nyelv utánit. Az archaikus énemet, akinek még soha nem volt szüksége beszédre, és a transzcendentális énemet, aki a teljesség reményében vagy a tökéletesség érdekében föladta konvencionális beszédkényszerét. Saját énemben még ez a szint áll a legközelebb az ő semleges látásához, mert nem zavarja meg a saját semleges látásomat a szabad működésben.

Az értelemnek van olyan szintje, amely a semleges látásnak megfelel.

„Nem tudom, mit értsek Keserü Ilona művein” – írja róla nyersen Tandori.

A kapitális problémával, amit Keserü életműve megnevez, ő is frontálisan ütközik. Mondhatná azt is, hogy nem tudja, mit ne értsen Keserü művein. Mindkét mondat azt jelentené, hogy a látás bizonyára más természetű dolog, mint az értés. Az emberi elme más szintjén működik, másik emeleten. Emeletek és féltekék kívánatra nem lecserélhetők. Az agytörzsön a képet úgy rögzítem, akár úgy raktározom el, hogy közben sem a bal oldali féltekét, sem a jobb oldali féltekét nem veszem feltétlenül igénybe, sem érzelmet, sem intellektust, s nem is végzem el velük sem az értelmezés, sem az értékelés munkáját. Tandori kijelentése talán nem annyira Keserü festészetére, hanem a befogadás kényszerítő erejére vonatkozik. Elmémnek nem tudom más helyén befogadni, mint ahol ő megcsinálta. S az ember csak elképedve áll a tény előtt, hogy festészetének ezt az analitikus alapvonását, kognitív fogantatását már egyik korai kiállítását megnyitó mestere, Martyn Ferenc ilyen világosan látta: „Megegyeztünk – mert a tanításból az oktató éppúgy okul, mint a tanítvány – megegyeztünk kezdetnek abban, hogy a rajz vizuális viszonylatok egyensúlya, annak módszere a szerkesztés, a szerkezet, ennek meg alapja a világosan fogalmazó értelem.” Őrületes megegyezés mester és tanítvány között. Tanítvány és mester olyan pályát anticipálnak, amelynek még nincsenek meg a módszerei és tárgyai, de mindketten látják azokat a képi jeleket, amelyek ezeket a tárgyakat és módszereket majd kihívják, mintegy kikényszerítik a tanítvány életéből.

Tandori mondata, vagy akár a mondat ellentettje a határvonalat jelöli ki, amely a dolgok fogalmi felfogása és a dolgok képi felfogása között húzódik. S ilyen értelemben határozott kritikai szembefordulás egy olyan műértelmezési hagyománnyal, amely történeti és szociológiai fogalmak közé helyezi a műtárgyat. Mintha erőszakosan átcibálná egy olyan emeletre, ahol csupán dekoratív jelentése lesz.

A kapitális probléma az újkori tudománytörténetben is fölmerül. Amikor világossá válik, hogy egzaktnak tekintett tudományos igazságok (még matematikai igazságok is) szociális kontextusban fogannak, konvenciókat követnek, ideológiák igazolásai vagy cáfolatai. Illetve vannak egymás mellett élő tudományos igazságok, amelyek nem hozhatók egymással összefüggésbe. Ami azt jelentené, hogy a világban nem létezik végleges és követhető rendezettség, bármily Istentől való elrendezettség sem, bár kétségtelenül vannak olyan dolgok, amelyek összefüggésbe hozhatók egymással és így beállíthatók egy önálló szerkezetbe. Amikor kiderül, hogy az általános relativitáselmélet és a kvantumelmélet nem egyeztethetők, inkommenzurábilisek, s vannak további tudományos igazságok, amelyek érvényessége csupán az egyik vagy a másik elmélet szerkezeti keretében vizsgálható. Pályája előre belátott hajnalán Keserü olyan tárgyakban tér vissza a festészeti alapkutatáshoz, amelyeket a festészet addigi története olyan konvenciónak tekintett, amivel kapcsolatban nincsenek, nem lehetnek kérdései. Ez a fénytörés és a test színe.

Tandorival ellentétben ezzel rögtön azt is mondanám, hogy Keserü művein nem csak a vizuális kontempláció, hanem még a fogalmi gondolkodás szintjén is bőségesen van mit érteni.

A fénytörés optikai jelenség, a test színe egyedi, genetikai adottság, s ő mintegy a személyes, az érzékileg észlelhető és a törvényszerű, az egyetemesen adott között keres viszonylatot. Színtannal, optikai jelenségekkel már korábban is feltűnően sokan foglalkoztak a magyar festészetben, s igen jelentős eredményekkel. Korniss, Gyarmathy, Vasarely, Veszelszky, Egry, Moholy-Nagy. S ugyanilyen feltűnő, hogy milyen sokan kerülték el eddig az érzéki tárgyakat. Czóbelen kívül nem tudnék festőt mondani, akit erotikus tárgyként, akár fétisként érdekelt volna az emberi bőr színe és mibenléte. Keserü ide állt be, a pregnáns érdeklődés és az átható hiány közé. Művészetének ez lett a szociológiai tere. Festői temperamentuma pedig fogalmi dichotómiákkal ábrázolható e térben, ahol egyszerre fog olyan tárgyakkal foglalkozni, amelyek a magyar festészeti hagyománnyal állnak kapcsolatban, illetve olyan tárgyakkal, amelyek legalább ilyen karakterisztikusan hiányoznak belőle.

Organikus és konstruktivista. Technikai és népművészeti. Természettudományos és etnográfiai. Aszkétikus és orgiasztikus. Amit mások ellentétként élnek át, ő komplementaritásában. Ha festői temperamentumát lélektani szinten akarjuk megvizsgálni, akkor azt mondhatjuk, hogy a magyar festészeti hagyományt még akkor sem hagyja el, amikor látja, hogy milyen terméketlen, s mily kevéssé alkalmas a megkapaszkodásra. Ilyen értelemben pozíciója szintén dichotómiákkal ábrázolható. Megtartó és felfedező, akadémikus és avantgárd. Ha festői kedélyét akarjuk leírni, akkor azt mondhatjuk, hogy olykor komoly, olykor hajlik a harsány paródiára, de nem ironikus. Festészetét nem a szépségre, hanem a gyönyörre építette. Nem analógiákban gondolkodik és nem asszociációkban, hanem mindkettőben egyszerre, ami gyakran leblokkolja.

Amint aztán szemrehányó és bosszús tekintete előtt ott álltam nagy pécsi műtermében a vakkeretre feszített vásznak között, saját beszédképtelenségemtől is tehetetlenül, s az agytörzsön rögzített képeket nem tudtam kapcsolatba hozni sem a jobb félteke, sem a bal félteke tartalmaival, amivel, most már bevallhatom, bizonyos kaján örömöt szereztem magamnak, Keserü mindenféle olvasnivalót keresett, mindenféle szövegeket a művészetéről. Ezekkel magamra hagyott. Mindössze néhány mondatot olvastam, aztán a Két szín-möbius alatt elaludtam a kanapén.

A firnájsz átható illata ébresztett. Amikor a szemem kinyitottam, már tudtam, mire fogom kinyitni. Egy immár ismerős képre, amely reggeli érkezésem pillanatában az állványon állt, s amivel kapcsolatban benne fölmerült, hogy értem-e egyáltalán, mivel foglalkozik. Azt viszont nem tudhattam előre, hogy ébredéskor mennyivel lesz kevesebb a fény, illetve miként változik, s a változás miként fogja a képet ismeretlen dimenzióiban megmutatni.

Ezen a képen a halállal foglalkozik. Ezt válaszolhattam volna, ha még jobban megszorít. De eszem ágában nem volt egy ilyen banális szót kimondani. Hiszen e kép előtt ugyan mit is jelentene. Egy testszínekből fölépített, s nála szokatlan módon erősen térbe állított csőrendszer volt a képen, valami csőgubanc. Lehettek volna testesen szigetelt fűtésvezetékek, de nem voltak azok. Vagy belek, de nem voltak belek, hanem erek, még leginkább vérerek. Végtelenített szülőcsatorna. Mindezt gondolhattam volna, de nem gondoltam. Nyelv előtti gondolkodása gyönyörteljes élményeit nem fordítja magában az ember. Mindenesetre felismertem annak a festői tulajdonságának egy újabb variánsát, miszerint képes kívülről nézni a saját bensejét.

Mágikus pillanat volt az ébredés.

Neutral vision in the painting of Ilona Keserü

Keserü is the master of neutral sight, and neutral sight can dispense with both the interpreter and interpretation. This is the level which her works bring into play, the state of the mind that predates and antedates language, my archaic self, who has never had need for language, as well as my transcendental self who, in the hopes of achieving completion or in the interest of perfection, has relinquished the conventional need to speak. This is the plane of my self that is closest, I think, to her neutral sight, because it does not interfere in the workings of my own neutral sight.

The mind has a plane that is the equivalent of neutral sight.

“I don’t know what I mean by the works of Ilona Keserü”, the writer Dezső Tandori has commented once.

Keserü herself clashes head on with the pivotal problem that her oeuvre addresses. She could easily say that she does not know what she does not mean by the works of Ilona Keserü. Both sentences would mean that seeing is of a different mature than understanding. It functions on a separate stage, or level, of the human mind. Stages and hemispheres cannot be changed at will. I fix the image on the brain stem, storing it without necessarily bringing either the right or left, hemisphere of the brain into play, and this also goes for my emotions and my intellectual capacities, nor do I put them in the service of interpretation or qualification. Possibly, Tandori’s comment says less about Keserü’s art than the compelling nature of interiorization. The only place in the brain where I can interiorize it is identical to the place where she made it. One cannot help but admire the clear-sightedness of the painter Ferenc Martyn, who said the following at one of her first exhibitions with regard to this analytical aspect, or basis, of her works, their cognitive source: “We agreed at the start—because the teacher learns as much from teaching as the pupil—in short, we agreed that drawing involves the balance of visual relationships, and that its means is structure, or structuring, and that structure relies on an intellect capable of composing in a clear manner.” What concordance between master and pupil! Both had anticipated a career whose methods and subjects had not yet been worked out. But both could identify those visual signs that would subsequently call them forth, veritably out of the life of Martyn’s pupil.

Tandori’s statement, or even the statement’s antithesis, marks the demarcation line that stretches between the conceptual understanding and the visual comprehension of things, and to this extent it stands in blatant opposition to the tradition of art interpretation that speaks of art in terms of historical and sociological concepts. By force, it drags art to a level or sphere where it will bear only with decorative significance.

This pivotal problem also comes up in the history of modern science the moment we realize that scientific truths, which we take to be exact and self-evident (including mathematical truths), are based in social contexts and adhere to certain conventions, or else are used to bolster or refute certain ideologies. There are scientific evidences that exist side by side, yet cannot be brought under one common denominator. Which means that there is no final “and”.

There are scientific truths existing side by side that cannot be brought under a common denominator. This would mean that there is no final and comprehensible order in the universe, not even orderliness created by any god, though needless to say, there are things that can be brought under a common denominator and can thus be situated within an independent structure. Furthermore, as we know, the general theory of relativity and quantum theory are not congruent but incommensurable, and there are other scientific truths as well whose validity depends on being studied within the framework of one or another theoretical construct. At the dawn of her career, Keserü turned back to the basic research into the nature of painting using subjects that the history of art to date had regarded as part of a convention that it did not question, nor did it have a mind to. These are refraction and body color.

Counter to Tandori, having said this I would also like to say that there is much that can be meant or understood in Keserü’s works, not only on the level of visual contemplation, but also on that of conceptual thinking.

Light refraction is an optical phenomenon, while body color is a unique, a genetically given, and she is searching for the relationship between the personal, what can be comprehended through the five senses, and what is the law of nature, the universally given. Much work has been done with the study of color and optical phenomena in general even before Keserü, and with good results, by artists such as Dezső Korniss, Tihamér Gyarmathy, Victor Vasarely, Ferenc Veszelszky, József Egry, and László Moholy-Nagy, to name a few. It is surprising how many painters have engaged themselves in this endeavor. But it is equally surprising how many have avoided sensual subjects. Except for Béla Czóbel I can think of no other painter who treated the color and essence of skin as an erotic object, not to mention a fetish, on its own merits. This is where Keserü positioned herself—between the fervent interest and the penetrating absence. We might call this the sociological space of her art, and in this space, where she was later going to treat subjects that are related to Hungarian traditions in painting, as well as subjects that are just as traditionally absent from said traditions.

Organic and constructivist. Technical and folk artistic. Partly relying on the natural sciences, partly on ethnography. Ascetic and orgiastic. What others conceive of as opposites, Keserü sees as complementary. If we wish to understand her artistic temperament on the level of psychology, we could say that she does not abandon the Hungarian tradition in painting even when she sees how infertile it is, and how ill suited it is to hang on to. To this extent, too, her position is characterized by dichotomy. She preserves and she discovers, she is academic and she is avant-garde. If we wish to describe her mood as a painter, we might say that at times she is serious, at times partial to shrill parody, but she is never given to irony. She has based her art not on beauty, but on pleasure. She does not think in terms of analogies and associations, but in terms of both at one and the same time, which often paralyzes her.

And so, as I stood in front of the canvases on their stretcher frames there in her large studio in Pécs, under her reproachful and fretful gaze, made even more helpless by my own inability to speak and unable to bring the images stored in the brain stem into contact with the contents of either the right or the left hemispheres—which filled me with a modicum of malicious glee, to be sure—Keserü went in search of things for me to read, all sorts of texts about her art. Then she left me to fend for myself. I read a handful of sentences, then fell asleep on the couch under Two Color-Möbius. I was startled awake by the pungent smell of turpentine. As I opened my eyes, I knew what I would see—a picture by now familiar to me which, upon my arrival that morning was standing on the easel, and because of which she wondered whether I understood at all what she was about. What I didn’t know beforehand is that when I woke up there’d be so much less light, or that it would change, and how this change would affect the painting, placing it in unfamiliar dimensions.

The subject of the painting is death. This is what I could have said, had she urged me further. But I had no intention of letting such banalities pass my lips. What meaning could it have in front of such a painting? It represented a system of pipes built up of body colors and situated strikingly in space, something that is unusual for the artist. A bunch of twisted and intertwined pipes. They could have been heating pipes insulated with living matter. But they were not. Or intestines. But they were not intestines either but veins, or rather, arteries. An infinite birth canal turned in upon itself. I could have thought all of this, but I didn’t. One does not turn one’s pre-lingual pleasures in upon one’s self. Be that as it may, I discovered yet another variant of her painterly aspect, whereby she is capable of regarding her own inside from the outside.

Szín-Möbius · Color-Möbius

Részletek a Tavaszi Műhely címmel Pécsett, 1997-ben rendezett nemzetközi tudományos–művészeti konferencián elhangzott előadásból. A konferenciát Grüner György fizikus, akadémikussal a UCLA professzorával együtt szerveztük.

Excerpts from the paper I read at the international science and art conference held in Pécs in 1977 and entitled Spring Workshop. We organized the conference jointly with the physicist György Grüner, a member of the Academy of Sciences and a professor at UCLA.

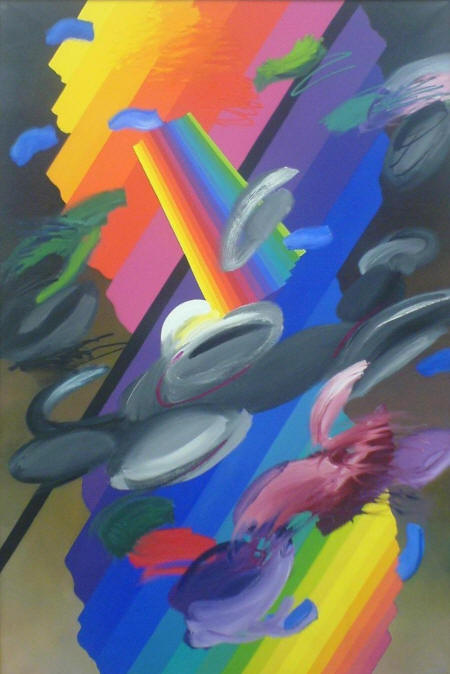

„…Visszatérve a szivárvány- vagy spektrumszínekhez, sok munkám készült, ahol a kép tárgya egyszerűen a színsor megfestése (pl. Színoszlop). A színek folytonossága jelenik meg a Vidovszky Lászlóval közösen létrehozott Hang–Szín–Tér-ben (1981, olaj, 123 műanyag csősíp, 300 × 1000 × 1000 cm, hangzó térberendezés), Mulandó végtelen színszalag-gubancában (1982, olaj, vászon, száraz rózsa, 80 × 120 × 3 cm).

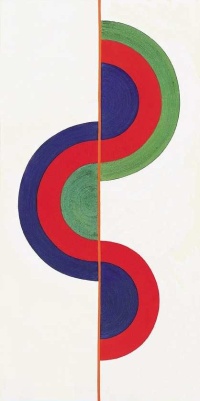

Más későbbi festményeken bonyolult összefüggések között a szivárványszínek együttese vagy szelete nyelvi összetevője, résztvevője a sokféle festészeti eszközt felvonultató kompozíciós együtthangzásnak. Közben egyszer csak megcsináltam a Szín-Möbiust (1987). Nyilvánvaló evidencia volt a létrejötte, de azt kell mondanom, sem én, sem más nem vette észre, hogy itt valami történt: ez ugyanis Találmány, és mindenképpen maga a kétszeres csoda. Az első, függesztett változat szerepel egy 1988-as videofelvételen, ami a műtermemben készült, és adásban is volt a Magyar Televízióban. Sokan látták, a második példány (1988, olaj, vászon, 60 × 80 × 120 cm) magántulajdonban van. Elgondolását és készítését – mint demonstrációs tárgyat – tanítottam hallgatóimnak az egyetemen.

A Möbius-formára mint csodaszerű matematikai térélményre korábban Keserü János építész hívta fel figyelmemet, szuggesztíven demonstrálta többféle variációs lehetőségét. Képzőművész kortársaim közül többen foglalkoznak a Möbius-témával. … Max Bill műveit természetesen láttam Budapesten a Műcsarnokban. Felfedezésem a végtelenített szín-sor és a térforma összekapcsolása volt 1987-ben, amelynek lényege, hogy az egyes színárnyalatok folyamatos egymásba kapcsolódással, határok és zökkenők nélkül, végtelen áramlással haladnak örökké a megfejthetetlen térben.

Évek óta tervezem a Szín-Möbius nagyméretű megvalósítását szabad- vagy belső térben, mint vékony lábakon álló, vagy statikailag a talajon kiegyensúlyozott, esetleg függesztett színes tér-alakzatot.

Konkrét helyszínek fotóiba montíroztam a Szín-Möbius változatait. Jó lenne mai épületekhez tervezni és megvalósítani (festett acéllemezből), a szalag szélessége 4–5 méter lehetne, a tér, amit bejátszik: 14 × 16 × 9 m, alatta át lehetne járni, de felülről is nézhető, esetleg keresztül lehet utazni rajta (Gigantikus lépték).

A Möbius-alakzat plasztikai megjelenése számtalan formai megoldást tesz lehetővé. Nagyméretű kivitelezésnél a formálást a felhasznált anyag, fém, fa stb. lemezfeszítő és a hajlítást megengedő természete befolyásolná. Az általam tervezett szín-forma variánsok többféle változat megvalósulását eredményezhetik úgy, hogy minden esetben egyedi mű készül.”

“… To return to the rainbow or spectrum colors, I made many pictures where the subject of the work was simply painting the rows of colors (e.g.: Color Column). The continuity of colors also appears in Sound—Color—Space, which I did jointly with László Vidovszky (1981, oil, 123 plastic flutes, 300 × 1000 × 1000 cm sound space installation), and in the infinite color ribbon tangle of Ephemeral (1982, oil on canvas, dried rose, 80 × 120 × 3 cm).

On later paintings, and among complex relationships, the rainbow colors used together or used partially, become the vernacular, the participant of the compositional consonance presented by the use of various painterly means. And in the meantime, I also managed to finish Color-Möbius (1987). It was inevitable, it seems. Still, I must say that neither I nor anyone else realized that something had happened: this is a Discovery, and certainly a double miracle in its own right. The first version, hung up, appears on a 1988 video made in my studio, and was shown on Hungarian Television. Many people saw it. The second version (1988, oil on canvas, 60 × 80 × 120 cm), is in a private collection. I taught what lay behind it and how it was made it to my college students, by way of demonstration.

The Möbius shape as a miraculous mathematical spatial construct had been pointed out to me earlier by the architect János Keserü, suggesting to me the possibilities for variation. Many among my contemporaries have occupied themselves with the Möbius strip. Naturally, I had seen the works of Max Bill at the Palace of Exhibitions in Budapest. My discovery in 1987 was how to connect a continuous row of colors with a spatial form, the gist of which is that with a continuous interconnection, the separate color shades advance for ever in a mysterious space without bounds and without hurdles.

For years I have been planning to create a large-size Color-Möbius either inside or in the open in the shape of a spatial form standing on narrow legs or firmly balanced, directly on the ground, or possibly suspended in space.

I mount versions of Color-Möbius on photographs of concrete places. It would be nice to design it to suit a modern building (made out of painted steel sheets). The width of the strip would be 4—5 meters, and the space it would take up 14 × 16 × 9 m, with a free passage under it for walking, but it could also be viewed from above, or possibly one could travel through it (Gigantic Scale).

The plastic realization of the Möbius strip gives scope for a multiplicity of formal solutions. In case of a large-scale Möbius strip, the shape would be influenced by the material used, metal, wood, etc., sheet-tensile, and the extent to which the material can be made to bend. The color and form variations I am planning are amenable to a number of ways of realizing them and in a manner so that regardless of which variation is made, it will be an independent piece of art.”

Utókép optikai jelenség · After-image optical phenomenon

Kiegészített részletek következnek az 1997 áprilisában Pécsett rendezett tudományos–művészeti konferencián elhangzott előadásom szerkesztett változatából.

What follows are excerpts from the edited text of the paper I gave at the scientific and art conference held in April, 1997 in Pécs.

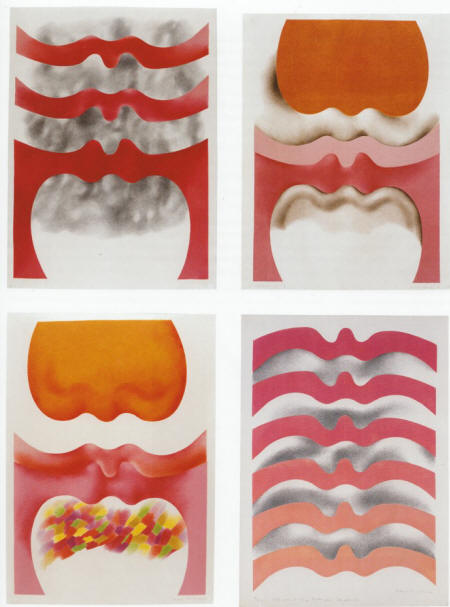

A nyolcvanas években egy másik optikai tünemény is foglalkoztatni kezdett, az utóképek világa. A lehunyt szemek mögött megjelenő látványra gondolok, ami az előzőleg erősen nézett sötét–világos, fény–árnyékjelenség nagyon intenzív fényszínekben megjelenő áttételes képe. Ennek a jelenségnek a feldolgozása lényegében egyszerű természettanulmány. Vagyis: elvben ábrázolni lehet egy utókép látványt ugyanúgy, mint egy látott tájat, arcot, szobabelsőt.

Az utókép úgy lett festői témám, hogy korábban sokat foglalkoztam a fénytörés tiszta színeivel, a festékből kikeverhető legnagyobb szín-intenzitással. A szemhéjon belüli látvány legerősebb szín-élményeim közé tartozik. Ráadásul mindig más alakzatokból áll, attól függően, ami a külső látványból előhívja. De azután is változik, ha behunyt szemmé figyelem, állandó mozgásban van kétféleképpen is: lassan felfelé száll, és színben folyamatosan transzponálódik. Így igazából mozgó médium kell a feldolgozásához, meg azért is, mivel a fényszínek: más színskála, mint amit a természetben érzékelünk, és ami pigmentekkel (színtestecskékkel) kikeverhető. A fény által átvilágított színes üvegablakos és a képernyő ragyogó fényszínei hasonlítanak hozzá. Az utókép látványok mozgó, hemzsegő, elúszó, világító, történő folyamatok. Mindez kábítóan szép. Mámorit, de egyben valóság, ami létezik. Nem biztos, hogy megragadható, tárgyiasítható, ábrázolható.

Az „utókép” azért is izgat, mert egyike a mindenkivel közös emberi, fizikai, érzéki tapasztalatoknak. Ugyanúgy, mint ahogy „csillagokat látunk”, ha beverjük a fejünket (ezek a csillagok egyébként szerintem kobaltkékek) vagy időnként „csöng a fülünk” Ezek abszolút közös emberi, testi tapasztalatok.

Két éve a Pécsi Tudományegyetem Művészeti Karán, Fodor Pál informatikussal közös kutatás keretében készült egy háromperces komputer-animáció egyik régi utókép-témám alapján. Ez a munka végtelenített formában látható volt képernyőn, 2002 őszén a Műcsarnokban rendezett Látás című kiállításon, együtt nagyméretű festményeimmel, amelyek, most a Ludwig Múzeum II. emeletén a 11-es teremben láthatók Utókép transzpozíció 1–2, és Tárgy és utókép címmel. A háromperces animációs tanulmány része M. Tóth Éva televíziós filmjének, melyet a Duna Televízió megbízásából utóképeimről 2002-ben készített.

A komputer-animációs kutatómunkát folytatjuk a közeljövőben az egyetemen. Megrendítő tapasztalatot jelentett számomra, hogy a számítógépes animáció segítségével megjeleníthetők olyan idegrendszeri, fiziológiai folyamatok eredményei, amelyeket tapasztalunk ugyan, de nem lokalizálhatók, demonstrálhatók mérésekkel.

In the 80s I became fascinated by another optical phenomenon, the world of afterimages. I am referring to the image seen behind closed eyelids, which is the highly intense, colorful transposition of the dark-light, light-shade phenomenon we have just concentrated our eyes on. To work with this phenomenon further we need only appeal to the natural sciences. In short: it is theoretically possible to represent an afterimage in the same manner as a seen landscape, face, or room interior.

The afterimage became a subject of my works because I had earlier occupied myself with the clear colors of refraction, with the greatest color intensity that can be obtained by mixing paint. What I see behind my closed eyes is among my most intense color experiences. Furthermore, it always takes different shapes depending on the external visual phenomenon. But it even changes as I regard it with closed yes, it is in constant motion in two different ways: it slowly rises upwards, and its colors are continuously transposed. Accordingly, it takes a moving medium to record it, and also because the colors of light move along a different color scale than what we grasp with the senses in nature, and what can be attained by mixing pigments (tiny color bodies).The colorful glass window panes impregnated by light and the bright colors of the light on a TV screen are like it. What we see as afterimages are moving, teaming, floating, light-projecting, here and now processes. It is all so enchantingly beautiful. Ecstatic, but also reality, what is. It is not necessarily tangible or amenable to being objectified and represented.

Two years ago at the Technical Faculty of the University of Sciences of Pécs, the informatics expert Pál Fodor and I prepared a three-minute computer animation based on one of my old afterimages. This video was on display in the fall of 2002 at the exhibition entitled Sight, held at the Palace of Exhibitions along with my large-size paintings which can now be seen in Room 11 on the second floor of the Ludwig Museum under the title After-Image Transposition 1–2 and Object and After-Image. The three-minute video forms part of Éva M. Tóth’s TV film which she made of my afterimages in 2002 for Duna Television.

In the near future we will continue the computer-animation work at the university. It was a staggering discovery for me that with the help of computer animation it is possible to show the results of neurological and physiological processes which we sense but which cannot be localized or demonstrated by measuring.

Ilona Keserü Ilona

A kiállítás termei · The Rooms of the Exhibition

Two Color-Moebius · 1987–1989 · oil on canvas · 70 × 70 × 20 cm

A Glimpse into Time 2 · 1992 · oil on canvas · 90 × 180 cm · Modern Magyar Képtár, Pécs

The Battle of Vezekény 1652 · 2003 · oil on canvas, mixed technique · 150 × 180 × 6 cm

Enigma · 1999 · oil on canvas · 200 × 200 cm · Péter Antal’s Collection

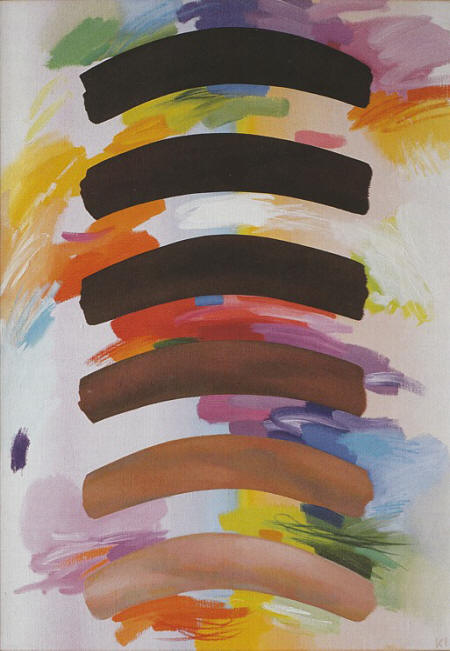

All 2 · 1981 · oil on canvas · 100 × 60 cm · Nádler István’s Collection

Space in the making 5–6–7–8 · 1971 · colored pencil on paperprint · 63,5 × 45,5 cm each · Modern Magyar Képtár, Pécs

Enigma · 1999 · oil on canvas

Form and After-Image · 1989–93 · oil on canvas · 220 × 130 × 19 cm

Form in Big Space · 1962 · oil on cardboard · private collection

After-Image Transposition II · 2002 · olaj, vászon · 150 × 180 cm

Nothing is Noways. Hommage to Géza Ottlik 1 · 1990–1997 · oil on canvas · 200 × 140 cm · Péter Antal’s Collection

Ottlik Géza · Géza Ottlik